Is the growing skepticism on SMS warranted? One of the most rewarding aspects of running this company has been our International Fellows Program which invites developers from all over the world to Uganda to work alongside our staff as peers. The following post was written by one of our recent Fellows, Oliver Christopher Kaigwa Haas (we called him Ollie) who now works at Frog Design.

“SMS till you drop!” A phrase that reflects well, the growing popularity of the 160-character text message in Africa. As is often the case with the implementation of simple technologies in low-resource settings, the creativity that has stemmed out of the use of SMS on this continent is truly amazing. As mobile phones become increasingly ubiquitous across Africa, SMS technology is being used to provide a host of innovative services in the health, financial and education sectors. While I am very excited about these developments, I have recently become increasingly sceptical about the potential for SMS to bring about a true revolution in end-user mobile technologies and applications in Africa.

Initially, I was incredibly excited about the opportunities presented by the SMS platform, as they related to economic development and empowerment, access to information and improved health systems in low-resource settings. I started to become involved in a number of SMS-based initiatives, including the FrontlineSMS:Credit organization, which “aims to make every formal financial service available to the entrepreneurial poor in 160 characters or less.” FrontlineSMS:Credit is an extension of the increasingly popular FrontlineSMS tool, which allows for mass-management of incoming and outgoing SMS messages through a simple computer-based interface and a single phone tethered to a laptop. The Credit initiative marries this technology with mobile money systems, which allow for the transmission of money by SMS and are being offered by an increasing number of mobile network operators in Africa.

The excitement for working on SMS-based projects in developing countries was also one of the main driving forces behind my decision to apply for the Appfrica Fellows program (see previous blog post). Here, I worked on the initial development of an SMS-based system for delivering medical test results in low-resource settings called ResultsSMS. Through my research in developing this system, along with direct exposure to a number of SMS services in Uganda and discussions with developers, entrepreneurs and students in the country, I started to wonder about the true power of SMS in revolutionizing end-user mobile technologies in the region.

I fear that focusing so much effort on development for the SMS platform by all stakeholders ranging from mobile phone manufacturers, network operators, NGOs and local entrepreneurs may stagnate the market at an “inefficient equilibrium”. Such equilibriums are common in technological markets, where VHS tapes and the QWERTY keyboard, for example, managed to achieve widespread market adoption despite the existence of superior alternatives at the times of their release.

This equilibrium may act as a barrier to potentially revolutionary developments in end-user mobile technologies in developing countries. Yes, we are currently presented with new SMS-based services on an almost daily basis, however, these are all restricted to interacting with 160 characters and require paying for information on a per-transaction basis (i.e. per SMS). These two main limitations also act as barriers to the widespread adoption of existing SMS-based services.

Take Google SMS, for example. As the name suggests, this service extends the reach of Google’s search functionality to SMS-only phones, “so anyone with a single bar of coverage and a phone has access to a lot of knowledge in their hands.” (White African) The initiative, which was developed in cooperation with the Grameen Foundation, is the result of extensive user studies in the region and provides customers on the MTN network with the following services:

- Google SMS Tips (Provides relevant and actionable information on sexual & reproductive health, clinic locations, as well as agriculture pests and diseases.)

- Google SMS Search (Gives users access to local and international news, sports scores and word definitions.)

- Google Trader (A marketplace application that allows you to buy and sell goods and services on your phone using SMS.)

Now, I am not criticising Google SMS per se, as it provides information that might be difficult or impossible to obtain elsewhere in rural areas in developing countries. It’s potential for receiving true widespread adoption is limited, however, by the fact that each SMS query sent to the service costs between 110 and 220 Ugandan Shillings (UGX). Google is already subsidizing Google SMS Tips, which is targeted primarily at low-income rural users, to reach the 110 UGX price point.

To truly understand this limitation, just think about how you or I perform a basic Google search. Very rarely do we find what we are looking for on the first try and, instead, it might take three or four queries to get to the right information. Assuming similar search behaviours in the Ugandan market, this would result in a cost somewhere closer to 400-800 UGX. Putting this in perspective, a basic local dish in Uganda may cost around 1000 UGX, which suggests that a simple Google search might cost around a half of what a low-income family pays for dinner.

Spinning this another way, my Appfrica colleagues and I estimated the average price of mobile data (GPRS) on Uganda’s mobile networks to be somewhere around 2 UGX/KB. This means you could send the equivalent of a small image or around 100,000 characters in plain text format; that’s more than 600X increase in the amount of textual information for the same price of a single Google SMS query.

I may sound naïve by suggesting that existing SMS-based services in developing countries should instead be provided through mobile data networks. The market penetration of data enabled handsets is simply too low and they are definitely not currently accessible to those living at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP). I do believe, however, that the true revolution in end-user mobile applications for low-resource settings will come about when these handsets become more accessible to a larger proportion of the population. Some of the puzzle pieces are already in place, as GPRS/EDGE networks do exist across most of Uganda’s mobile coverage area. In addition, Java™ and data enabled phones are already becoming a common sight in larger cities within the country. Current mobile applications and servicesl, however, do not take full advantage of these platforms.

The mobile phone market in Africa definitely still needs time to mature and smart phones that are priced at an appropriate level to target the majority population in this region are still far off. Let’s hope, however, that the current focus on SMS development does not create a negative feedback cycle in which mobile developers and operators stay locked to this limited platform. Such “stagnated development” is already somewhat apparent in the market for low-price handsets, as described by Ken Banks in his post on Kiwanja.net:

“In February 2010 Vodafone announced ‘the world’s cheapest phone’. At $15 it certainly scores low on the price tag – which is good – but it also scores low on functionality – not so good. Not only is this a problem for any end user who might need (or want) to use it for things beyond voice calling and SMS, but it’s also perpetuating a long-standing problem in the social mobile world dating back over five years.” (Kiwanja.net)

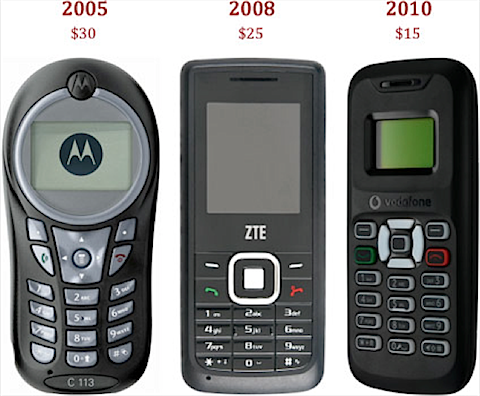

The article goes on to profile three popular “emerging-market” handsets, which show a clear drop in price between 2005 and 2010 (see image). The functionality of these handsets has largely stagnated over these five years, however, with none of the phones providing basic data functionality or java-enabled downloadable applications. It would be interesting to see some development focused on keeping a $25 price tag, for instance, and maximising functionality at this price level. Such a phone would still be inaccessible to a large percentage of the population in emerging markets, however, I believe this could start pushing the market in the right direction. Data and Java™ enabled phones will allow for the development of richer and more usable applications that will provide almost limitless potential beyond 160 characters of text.

The Motorola C113, a popular ZTE (a Chinese Manfacturer) that was widely available in East Africa in 2008 and the brand new $15 Vodaphone 150. Although the prices of these “emerging market” handsets has dropped over the last five years, functionality has largely stagnated. (Photo credit: Kiwanja.net)

http://whiteafrican.com/2009/06/29/new-sms-services-in-uganda-from-grameen-google/

http://google-africa.blogspot.com/2009/06/google-sms-to-serve-needs-of-poor-in.html

http://mobileactive.org/google-launches-health-and-trading-sms-info-services-uganda-high-price

http://manypossibilities.net/2009/04/mobiles-in-africa-we-need-the-eggs/

http://www.90percentofeverything.com/2009/10/14/achieving-adoption-of-a-disruptive-product/

Photo by mejymejy used under the Creative Commons

On Love and Hate for 160 characters

Is the growing skepticism on SMS warranted? One of the most rewarding aspects of running this company has been our International Fellows Program which invites developers from all over the world to Uganda to work alongside our staff as peers. The following post was written by one of our recent Fellows, Oliver Christopher Kaigwa Haas (we called him Ollie) who now works at Frog Design.

“SMS till you drop!” A phrase that reflects well, the growing popularity of the 160-character text message in Africa. As is often the case with the implementation of simple technologies in low-resource settings, the creativity that has stemmed out of the use of SMS on this continent is truly amazing. As mobile phones become increasingly ubiquitous across Africa, SMS technology is being used to provide a host of innovative services in the health, financial and education sectors. While I am very excited about these developments, I have recently become increasingly sceptical about the potential for SMS to bring about a true revolution in end-user mobile technologies and applications in Africa.

Initially, I was incredibly excited about the opportunities presented by the SMS platform, as they related to economic development and empowerment, access to information and improved health systems in low-resource settings. I started to become involved in a number of SMS-based initiatives, including the FrontlineSMS:Credit organization, which “aims to make every formal financial service available to the entrepreneurial poor in 160 characters or less.” FrontlineSMS:Credit is an extension of the increasingly popular FrontlineSMS tool, which allows for mass-management of incoming and outgoing SMS messages through a simple computer-based interface and a single phone tethered to a laptop. The Credit initiative marries this technology with mobile money systems, which allow for the transmission of money by SMS and are being offered by an increasing number of mobile network operators in Africa.

The excitement for working on SMS-based projects in developing countries was also one of the main driving forces behind my decision to apply for the Appfrica Fellows program (see previous blog post). Here, I worked on the initial development of an SMS-based system for delivering medical test results in low-resource settings called ResultsSMS. Through my research in developing this system, along with direct exposure to a number of SMS services in Uganda and discussions with developers, entrepreneurs and students in the country, I started to wonder about the true power of SMS in revolutionizing end-user mobile technologies in the region.

I fear that focusing so much effort on development for the SMS platform by all stakeholders ranging from mobile phone manufacturers, network operators, NGOs and local entrepreneurs may stagnate the market at an “inefficient equilibrium”. Such equilibriums are common in technological markets, where VHS tapes and the QWERTY keyboard, for example, managed to achieve widespread market adoption despite the existence of superior alternatives at the times of their release.

This equilibrium may act as a barrier to potentially revolutionary developments in end-user mobile technologies in developing countries. Yes, we are currently presented with new SMS-based services on an almost daily basis, however, these are all restricted to interacting with 160 characters and require paying for information on a per-transaction basis (i.e. per SMS). These two main limitations also act as barriers to the widespread adoption of existing SMS-based services.

Take Google SMS, for example. As the name suggests, this service extends the reach of Google’s search functionality to SMS-only phones, “so anyone with a single bar of coverage and a phone has access to a lot of knowledge in their hands.” (White African) The initiative, which was developed in cooperation with the Grameen Foundation, is the result of extensive user studies in the region and provides customers on the MTN network with the following services:

Now, I am not criticising Google SMS per se, as it provides information that might be difficult or impossible to obtain elsewhere in rural areas in developing countries. It’s potential for receiving true widespread adoption is limited, however, by the fact that each SMS query sent to the service costs between 110 and 220 Ugandan Shillings (UGX). Google is already subsidizing Google SMS Tips, which is targeted primarily at low-income rural users, to reach the 110 UGX price point.

To truly understand this limitation, just think about how you or I perform a basic Google search. Very rarely do we find what we are looking for on the first try and, instead, it might take three or four queries to get to the right information. Assuming similar search behaviours in the Ugandan market, this would result in a cost somewhere closer to 400-800 UGX. Putting this in perspective, a basic local dish in Uganda may cost around 1000 UGX, which suggests that a simple Google search might cost around a half of what a low-income family pays for dinner.

Spinning this another way, my Appfrica colleagues and I estimated the average price of mobile data (GPRS) on Uganda’s mobile networks to be somewhere around 2 UGX/KB. This means you could send the equivalent of a small image or around 100,000 characters in plain text format; that’s more than 600X increase in the amount of textual information for the same price of a single Google SMS query.

I may sound naïve by suggesting that existing SMS-based services in developing countries should instead be provided through mobile data networks. The market penetration of data enabled handsets is simply too low and they are definitely not currently accessible to those living at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP). I do believe, however, that the true revolution in end-user mobile applications for low-resource settings will come about when these handsets become more accessible to a larger proportion of the population. Some of the puzzle pieces are already in place, as GPRS/EDGE networks do exist across most of Uganda’s mobile coverage area. In addition, Java™ and data enabled phones are already becoming a common sight in larger cities within the country. Current mobile applications and servicesl, however, do not take full advantage of these platforms.

The mobile phone market in Africa definitely still needs time to mature and smart phones that are priced at an appropriate level to target the majority population in this region are still far off. Let’s hope, however, that the current focus on SMS development does not create a negative feedback cycle in which mobile developers and operators stay locked to this limited platform. Such “stagnated development” is already somewhat apparent in the market for low-price handsets, as described by Ken Banks in his post on Kiwanja.net:

“In February 2010 Vodafone announced ‘the world’s cheapest phone’. At $15 it certainly scores low on the price tag – which is good – but it also scores low on functionality – not so good. Not only is this a problem for any end user who might need (or want) to use it for things beyond voice calling and SMS, but it’s also perpetuating a long-standing problem in the social mobile world dating back over five years.” (Kiwanja.net)

The article goes on to profile three popular “emerging-market” handsets, which show a clear drop in price between 2005 and 2010 (see image). The functionality of these handsets has largely stagnated over these five years, however, with none of the phones providing basic data functionality or java-enabled downloadable applications. It would be interesting to see some development focused on keeping a $25 price tag, for instance, and maximising functionality at this price level. Such a phone would still be inaccessible to a large percentage of the population in emerging markets, however, I believe this could start pushing the market in the right direction. Data and Java™ enabled phones will allow for the development of richer and more usable applications that will provide almost limitless potential beyond 160 characters of text.

The Motorola C113, a popular ZTE (a Chinese Manfacturer) that was widely available in East Africa in 2008 and the brand new $15 Vodaphone 150. Although the prices of these “emerging market” handsets has dropped over the last five years, functionality has largely stagnated. (Photo credit: Kiwanja.net)

http://whiteafrican.com/2009/06/29/new-sms-services-in-uganda-from-grameen-google/

http://google-africa.blogspot.com/2009/06/google-sms-to-serve-needs-of-poor-in.html

http://mobileactive.org/google-launches-health-and-trading-sms-info-services-uganda-high-price

http://manypossibilities.net/2009/04/mobiles-in-africa-we-need-the-eggs/

http://www.90percentofeverything.com/2009/10/14/achieving-adoption-of-a-disruptive-product/

Photo by mejymejy used under the Creative Commons